ON THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE MIGRANT WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO CORFU

By

Dr Anthony Stevens

Biographical note: A graduate of Oxford University in Medicine and Psychology, Dr Stevens is an internationally recognized authority on the new discipline of Evolutionary Psychiatry and on the Analytical Psychology of Carl Gustav Jung. He is the author of over a dozen books on these subjects, many of which have been translated into a number of different languages. He is a Member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, and of the International Association for Analytical Psychology. In 1975 Oxford University awarded him a Doctorate in Medicine for his research on infant attachment behaviour conducted at the Metera Babies Centre in Athens. He retired to Corfu in 2002 and has lived there very happily ever since.

Madam President, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I have been given a huge subject, and instead of 30 weeks to discuss it with you I have been given 30 minutes! So I’m going to have to be selective, to put it mildly. I hope you will forgive me if I don’t even attempt to talk about the economics or politics of migration, but confine myself to three psychological questions: (1) Why do we migrate? (2) Why do so many of us migrate to Corfu? And (3) Why do we, like Albert Cohen, occasionally suffer from a nostalgia to return to our place of origin?

At the present time Corfu is home to a lot of foreigners: about 30 thousand of them! 15,000 from countries in the European Union, and another 15,ooo from non-EU countries, including eighty different countries, as well as an indeterminate number of Africans who subsist on what they earn from selling pirated DVDs on the Liston. This means that a fifth of the total population of Corfu (150,000) consists of foreign immigrants.

The British, and for that matter, the Greeks, have always been great migrants. But now the traffic is in both directions, and both countries are having to cope with a large and growing inflow of immigrants - as well as with other major economic, social and political problems of which we are all too aware.

In terms of outgoing migration Britain has the highest rate among Europeans countries, and more than 3 million Britons are living abroad at the present time. A recent survey found that 52% of the British population would like, if they could, to migrate.

What makes us do it? Why do we give up the security of our homeland for a foreign land?

Sociologists who study migration make a distinction between push factors and pull factors. The push factors are responsible for what we might call the migration of escape - escape from the miseries of economic hardship, from religious or political persecution, as well as from boredom, from social maladjustment and psychological despair.

The pull factors can be grouped under one heading: the desire to find something better.

The choice of where we migrate to is never entirely determined by economics or politics but also by mythology. All human communities have myths which unconsciously influence the behaviour and ideals of the people who share them. This is very true of migration myths. Examples readily come to mind: the British myth of Empire Building as a “civilizing mission”which in the 19th century resulted in a quarter of the planet being ruled from London, the Aryan myth of Lebensraum to be conquered by force which resulted in two world wars, the American myth of the ever extending frontier (“Go West young man!”), and the South American myth which prevailed before the Christian missionaries got there of “the Land without Evil”. In terms of the Biblical myth at the root of our Western civilization, what we are seeking when we migrate is our own version of “The Promised Land”, a paradise flowing with milk and honey.

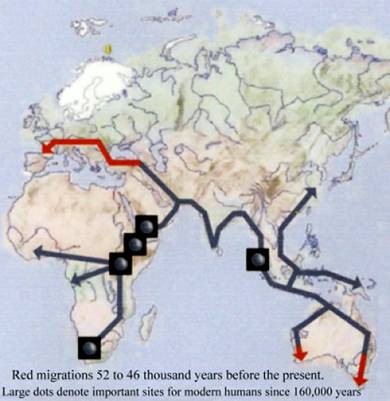

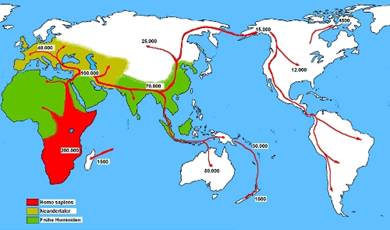

The first point I want to make is that we are all migrants. Migration is what we humans do, and we’ve been doing it for an awfully long time. We, Homo sapiens sapiens, are the descendants of migrants who left Africa within the last 200,000 years. But this was the second African diaspora. There was at least one earlier exodus about a million and a half years ago, when our predecessor, Homo erectus, moved out of Africa to colonize parts of the Middle East and Asia. If we go back two million years, we are all Africans.

Early human migrants all kept close to one indispensable commodity: water. Our ancestors passed down the Nile Valley into Eurasia, along the shores of the Indian Ocean to make the daunting 60 mile sea crossing between Timor and Greater Australia.

We humans have always been great travellers. And since we evolved the capacity to move about on two legs, our hands have been free to carry weapons, food, and possessions. Our quick brains have enabled us to cross mountains, seas, and deserts, make shelters, clothes and fires to warm ourselves and cook food. As a result we have been able to spread out over the planet to settle in widely differing climates and places, thus outwitting every other species on earth. Our triumphant success as a species, in other words, depends on our willingness to migrate.

We are never more truly ourselves than when we are travelling to new destinations. Why else should we spend so much time developing ever more efficient means of transport? And why is it when we are free to go on holiday, we travel, we go on a journey? Planning a holiday in some warm sunny place with inviting seas and lush vegetation, and setting off on the journey to find a temporary paradise is one of the primary pleasures of contemporary life, and it is a pleasure on which the economy of Corfu depends.

And when people have sampled Paradise on holiday they long to possess it permanently - which is what many of the 30,000 foreign visitors have done in Corfu.

But it must be admitted that not everyone who comes here is looking for a paradise of peace and tranquility. Some have other things in mind.

“What”, says this indignant migrant to God, “Milk and honey? We were hoping for fleshpots!”

We ourselves also provide a means of transport in the form of our own bodies. According to the biologists, we humans are all beasts of burden driven by our genes, which ride along inside us so as to satisfy their own selfish determination to get into the next generation of humankind. Our personal life and death is of no significance to the genes we carry: we are just their horses that they change at posting stages on the way.

Here you see an obsolete gene-carrier being sent off to the scrap yard in a hearse, while a new gene-vehicle is being delivered by a stork, suitably marked with a sign “Baby on board”.

But with all their talk of selfish genes, what the biologists sometimes forget is that we humans have conscious egos. To us it is the adventure of the journey that counts. The secret of living the good life is to enjoy the journey. As Cavafys advises Odysseus setting off on his voyage back to Ithaca: “να εύχεσαι να είναι μακρύς ο δρόμος, γεμάτος περιπέτειες, γεμάτος γνώσεις” “Wish that your journey be a long one, full of adventures, full of knowing.” Sometimes it is more blessed to travel than to arrive!

The journey is the great allegory of life.

For all of us, the journey of life is the heroic saga of leaving the familiar behind and progressing into the unknown future. Think of all those heroes in myths and fairy tales who act as role models for us all: they set out on a journey during which they encounter trials and ordeals which test their strength and their cunning as they proceed on their quest for some great prize: the beautiful bride, the kingdom, the treasure hard to attain, the golden fleece, the Holy Grail.

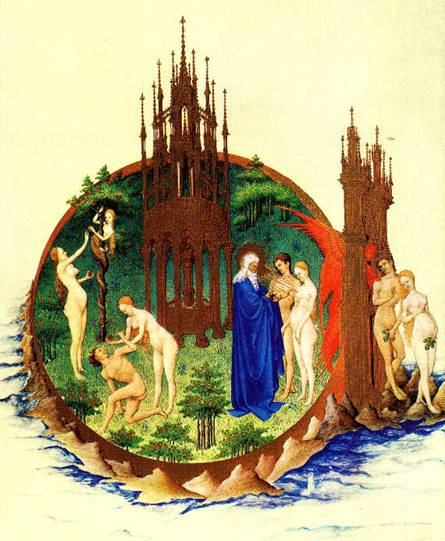

For us Europeans this archetypal quest is deeply imbued with the Biblical myths of the Garden of Eden, the Fall, and the journey to the Promised Land. We all recognize the Book of Genesis as a myth of cosmic creation. But it is more than that. It is also an allegory of human gestation in the womb and birth into the world.

Our first 9 months of life are spent in a gynecological paradise bounded by the containing wall of the womb. It is a paradise of comfort and ease. Everything that is needed is provided by the all-giving placenta and that physiological “Tree of Life”, the umbilical cord.

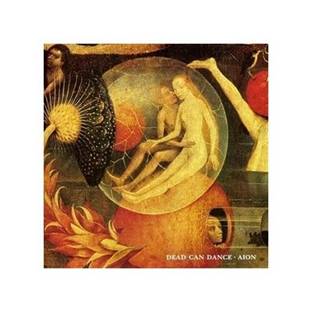

Mediaeval pictures often represented the Garden of Eden as a womb. There’s a profound psychological truth in that. The Garden of Eden is the archetypal womb of our culture.

Here we see Adam and Eve in the womb waiting to be born, as represented by Hieronymos Bosch.

Trouble starts when the birth contractions begin and the infant human being is expelled from this warm and tranquil womb of Eden into the appalling confusion of life outside.

And here are Adam and Eve out of the womb, which is now empty, except for the tree, ruled over by God:

Forced out into the world, they have to prepare themselves for the arduous journey of life. You notice the angel standing guard outside the Garden. Why is he there? To prevent them from getting back in. Why is he necessary? Because they long to get back. We all do. This is the archetypal nostalgia of our species - the longing to return to the womb, to the mother, to the source of our personal origin. But we can’t go back. We have to get on with the business of living.

Nevertheless, the dream of the Paradise Garden never entirely leaves us. And we dream of finding it either in this life or the next. We create fantasies of Utopia, of Heaven, of a Promised Land flowing with milk and honey, every bit as peaceful and perfect as the paradise womb from which we have been expelled. It is a dream that human beings share generation after generation, and it gives us the courage to go forward on the journey of life, to travel - to migrate. As Oscar Wilde remarked, “Maps which fail to show Utopia are useless, because it’s the one place that we all want to get to.”

If the cartographers cannot show us where a Utopian Paradise lies, at least the great artists of landscape have been able to show us what it is like: it is Arcadia.

It is richly verdant, it has stately trees, distant mountains, gentle nymphs, and always water. It is imbued with a sense of holy tranquility. Like a beautiful garden, it induces a delicious sense of “the peace that passeth understanding.”

This too has a fascinating evolutionary history. It is an idealized representation of the primordial landscape in which our species evolved high up in Central Africa - the landscape that geologists call savannah.

Savannah is the term they use to describe a grassland ecosystem with trees sufficiently widespread to prevent the canopy closing over it. This allows sufficient light to reach the ground to produce a fertile layer of soil supporting a great variety of grasses and plants.

Savannahs provide distant views, and a natural environment favourable to nomadic life: it has trees which offer protection from the sun and refuge from predators, and has plentiful sources of food.

Psychological experiments performed in different parts of the world have shown that landscapes which resemble the African savannah (in which we evolved) induce positive aesthetic responses in people. It seems very likely that our aesthetic responses to landscape are derived from evolved propensities that helped our hunter-gatherer ancestors make such crucial decisions as when to give up one location and migrate to another, where to settle, and what kind of places to avoid. These evolved psychological propensities are encoded in our DNA and are still alive in us: they influence our personal fantasies of paradise and the Promised Land and our choices of where to go on holiday and where to go to live.

Which brings me to my second question: Why do so many of us, particularly from Northern Europe, choose to migrate to Corfu? The main reasons, I think, are its climate, its physical nature, and its history. Corfu is Greek, a part of Greece, and so it has a powerful attraction for hellenophiles. Yet - thanks to the Venetians, ably assisted by St Spyridon - Corfu escaped the 400 year Turkish occupation which afflicted mainland Greece and as a result Corfu was able to experience the civilizing impact of both the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

This crucial historic fact is abundantly apparent in her architecture, her monuments, the civility of her people, and (until recently) in the wise management of her magnificent landscape. Hellenism - the love of all things Greek - has had a profound influence on English thought and literature for centuries. So that for an Englishman like myself, who has known and loved Greece for years, coming to live permanently in Corfu as I did 8 years ago, gave me a true sense of homecoming. It was as if I had returned to the cradle of our civilization to live out the final stages of my life.

As the English traveller Anthony Sherley wrote of Corfu in 1601:

“A Greekish isle, and the most pleasant place our eyes ever beheld ..... In our travels many times falling into dangers and unpleasant places, this only island would be the place where we would wish ourselves to end our lives.” Lawrence Durrell quotes this as an epigraph to his wonderfully evocative book about Corfu, Prospero’s Cell, which is responsible for bringing as many visitors and, indeed, migrants here as his brother Gerald’s My Family and Other Animals.

To be struck by the magic of Corfu is akin to falling in love. The crucial test of love is its staying power. Will it last? The initial infatuation has to be balanced by reality. When one moves in and lives with the beloved, her failings, as well as her beauties, become all too apparent with time. They have to be understood, appreciated, and forgiven if one’s love is to endure. The enchantment of life on this island can only be sustained by developing a philosophical attitude to the unsympathetic building developments of recent years, the careless disposal of garbage, the bureaucratic delays, the impossibility of parking in town. We mustn’t forget that there is always a snake in paradise! But these irritations are outweighed by the sublime beauties of the mountains, olive groves, meadows, and seascapes so lovingly painted by Edward Lear, by the warm friendliness of the people, the charming villages, and the incredible, operatic town.

On the first page of Prospero’s Cell, Lawrence Durrell introduces a psychological reason for why so many migrant’s end up in Corfu: “Other countries may offer you discoveries in manners or lore or landscape”, he writes. “Greece offers you something harder - the discovery of yourself.”

Ultimately, the Promised Land cannot be found in the outer world. It is an inner space that has to be experienced symbolically in our hearts. The psychological migrant is one attempting to escape from himself. He doesn’t get on with his compatriots because he doesn’t get on with himself. When he migrates in search of a happier life he takes his inner conflicts with him and recreates them anew wherever he tries to settle. Self-discovery, if he can achieve it, is the healing goal. Greece gives us Northerners the chance to be more real. To become the humans that we really are. It is a mystery that cannot be readily explained, only experienced.

Lawrence Durrell was certain that Shakespeare had Corfu in mind when he wrote The Tempest - the only one of Shakespeare’s plays entirely expressive of his own psychology. The isle is full, wrote Shakespeare, of “Sounds and sweet aires, that give delight, and hurt not.”

For many the Promised Land is a place of retreat: it is Prospero’s cell - the place one finds to withdraw from the hurly-burly of mundane existence in order to become reconciled with oneself, to find - if one is lucky - one’s own bit of paradise on earth as an inner landscape. This inner paradise is easier to find if the outer landscape is a richly abundant savannah echoing the primordial Eden of our origins.

Which brings me to my final question: Why do people like Albert Cohen who leave Corfu to migrate elsewhere suffer from a nostalgia to come back to it?

In a letter to the President of the Corfu Reading Society dated 9th January 1969, Albert Cohen wrote: “J’ai quitte Corfu en 1900, lorsque j’avais cinq ans, et je n’y suis retourne qu’une seule fois, a l’age de treize ans, pour deux semaines.... Malgré cet unique et très bref séjour, j’ai garde un souvenir si vivant de l’extraordinaire beauté de cette île que, si étrange que cela puisse paraître, il y a en moi une sorte de patriotisme corfiote très sincère. De cette île merveilleuse, je n’ai rien oublie, ni la mer Ionienne si belle, ni la forteresse vénitienne, ni la charmante Esplanade, ni Gastouri, ni Benitse, ni Analipsi, ni les petites ruelles du quartier juif. Dans mes romains “Solal” et “Mangeclous”, J’ai d’ailleurs rendu hommage a cette beauté de Corfou en donnant toutefois un autre nom a ma cher île natale.”

In another letter, Albert Cohen expresses his desire to return on a visit: “Ce serait pour moi une grande joie que ce pèlerinage dans ma chère île natale, qui a inspiré toute mon oeuvre...”

An important distinction has to be made between the refugee (the migrant who feels compelled to leave his place of birth) and the voluntary migrant who leaves as a matter of choice. Of the two, the refugee is more prone to the pangs of nostalgia, and in some cases it can be crippling - as indeed it was for many Russians who fled from St Petersberg in 1917 at the time of the October Revolution. For the rest of his life Sergey Rachmaninoff felt as if he were “ a ghost wondering forever in the world. I am burdened with a harvest of sorrow,” he said, “a burden unknown to me in my youth: it is that I have no country. Now that I am successful I can go anywhere I wish. But one place is closed to me: the country where I was born.” Eventually, he established a retreat for himself in a savannah landscape near Lake Lucern, with views of meadows, trees, mountains and water. “Here I believe I shall find peace at last,” he wrote. But the second world war drove him into exile once again. “Now,” he said, “I can only live in my music. And it is Russian music.”

Sergey Prokofiev suffered no less from the pangs of ‘paradise lost”, and in his case they were so powerful that they made him return to Russia and risk the horrors of Stalinist persecution. The drive to have one’s paradise restored can be so powerful as to overwhelm all other considerations. Perhaps Proust was right when he wrote: “Les seuls vrais paradis sont les paradis qu’on a perdu.”

English writers born in India, like Rudyard Kipling, Saki (H.H.Munro) and the Durrell brothers, who, deprived for whatever reason of that paradise of sunshine, colour and human warmth, never entirely got over it and had to create a substitute, richly imaginative world in their novels. In the case of the Durrells they also found their paradise in Corfu.

In my own case, where migration was entirely a matter of choice, I feel no nostalgia for my homeland. My heart has been successfully transplanted from England to Corfu. It is the magic of Corfu that made the transplant possible. For me, as for many others, Corfu - despite the snake - is both womb and paradise combined. A unique combination.