| The full text of a lecture entitled WHAT IS WAR AND WHY DO WE DO IT? given by Anthony Stevens at the Durrell School, Corfu, on July 4th 2007. | ||||

WHAT IS WAR AND WHY WE DO IT? I think we can all probably agree that the most terrible disaster that one group of human beings can inflict on another is war. Tsunamis, hurricanes, earthquakes and floods are bad enough, but these are not caused by human agency. Wars are - the loss of life, the appalling physical injuries, the wholesale destruction of towns, cities, crops and the proud achievements of history, the lasting psychological and emotional traumas suffered by the survivors - all cause misery on an indescribable scale. Yet we go on doing it to one another, generation after generation. Why?

What is war and why do we do it? A good definition of war is given by the American anthropologist, Anthony Wallace (1968): “War is the sanctioned use of lethal weapons by members of one society against members of another. It is carried out by trained persons working in teams that are directed by a separate policy-making group and supported in various ways by the non-combatant population. Generally, but not necessarily, war is reciprocal. There are few, if any, societies that have not engaged in at least one war in the course of their known history, and some have been known to wage wars continuously for generations at a stretch.” Some anthropologists have argued that the principles of war are so simple and so fundamental that peoples widely separated in space and time have apparently discovered some or all of them. As Professor Spaulding, writing between the wars in 1928, put it “War is war. Its outward forms change, just as the outward forms of peace change.....[But] strip any military operation of external, identifying details, and one will find it hard to put a place and date to the story.” Warfare is a recurrent and universal characteristic of human existence. The mythologies of practically all peoples abound in wars and the superhuman deeds of warriors, and preliterate communities apparently delighted in the recital of stories about battles. Since our species became literate a mere 5,000 years ago, written history has mostly been the history of wars. Practically all frontiers between nations, races, and religions have been established by wars and all previous civilizations perished because of them. The earliest records known to archaeology, apart from lists of utensils, are the records of war. Between 1500 B.C. and 1860 A.D. there were in the known world an average of thirteen years of war to every year of peace. In the 150 years between 1820 and 1970 the major nations of the world went to war on average once every twenty years-that is to say, once per generation (Walsh, 1976). Armed conflict, like sex, seems to be a primary obsession of mankind. And it is appropriate to use the generic term mankind since war has universally been a masculine creation. The anthropological and historical evidence is overwhelming: Women do not make wars; men do. However, there have always been both men and women of goodwill who have exerted their energies to prevent war - demonstrating a capacity within us for peaceful coexistence as well as armed belligerence. Thousands who knew war evidently sickened of it and dreamt of lasting peace, expressing their vision in literature and art, in philosophy and religion. They imagined Utopias freed of martial ambition and bloodshed which harked back to the Golden Age of classical antiquity, to the Christian vision of a paradise lost, and to the Arcadia of Greek and Latin poetry, so richly celebrated in the canvases of Claude and Poussin. All these things bear eloquent testimony to the human longing for peace, but they have not triumphed over our dreadfully powerful propensity to war. There have always been treaties and non-aggression pacts, but all have been equally unsuccessful in eradicating war. Between 1500 B.C. and 1860 A.D. more than 8,000 peace treaties were concluded. Each one of them was meant to remain in force forever. On average they lasted two years. Peace treaties do not create peace. They are a sign that peace has, for the time being, returned. The only principle that has been consistently applied is that of the Roman senate: “If you want peace, prepare for war.” The Russians have an old proverb: Eternal peace lasts only until next year. If alien anthropologists from another galaxy had been observing us over the centuries, they would have had no hesitation in defining us as a warlike species. But they would have to have acknowledged that we are a peace-loving species as well. It is as if war and peace come in cycles like the tides and the phases of the moon.. In a sense, war and peace are complementary concepts which qualify one another: war is inconceivable without peace, and peace inconceivable without war. A desire for peace becomes particularly salient, as it did in Europe in 1918 and again in 1945, at times when war exhaustion, destruction and grief have taken their toll. The attractions of war become more compelling the longer peace has prevailed In his book On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, Norman F. Dixon conceives of peace as a state in which our warlike propensities are sublimated or repressed. He points out that books and films dealing with war and violence become increasingly popular during prolonged periods of peace - like pornography following an age of sexual repression...” As John Rae put it in his novel The Custard Boys: “War is, after all, the universal perversion. We are all tainted: if we cannot experience our perversion at first hand we spend our time reading war stories, the pornography of war; or seeing war films, the blue films of war; or titillating our senses with the imagination of great deeds, the masturbation of war.” Much of the finest and most evocative writing about war has come not from academics and historians but from people who have actually lived through it, in reality or imagination, and recorded their responses in poetry, prose, and film. Creative artists tell us how war is. Their subject is war and the pity of war - as well as its triumphs and its glories. This vast, rich literature represents what I shall term the subjective response to war. What I’m trying to communicate in this brief talk is the objective, transpersonal view of war, a view that attempts to embrace the phenomenon of war as an all-too-human characteristic. A critical factor affecting how writers write about a particular war is the stage the war has reached at the time of writing. At the outbreak a surprisingly large number seem to be in favour, carried along by the excitement of the moment in a fervour of patriotic enthusiasm. Disillusionment sets in as the war progresses. Disillusionment reaches its climax when hostilities are over and there is time to reflect on what it has all cost. Take, for example, the collective experience of World War I in Europe from 1914 to 1918, so wonderfully evoked in Paul Fussell’s fine book The Great War in Modern Memory. The outbreak of this terrible war was greeted with rapturous enthusiasm in France, Britain, Germany, Russia, and Austria. Rupert Brook captured this brief moment of joy in his incredible sonnet celebrating the end of Peace:

Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power, To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping

Few, it seemed, dissented from this joyful anticipation of the carnage to come. Those who did found themselves in a despised minority: “I discovered to my amazement that average men and women were delighted at the prospect of war,” wrote Bertrand Russell (1967) in his Autobiography. “I had fondly imagined what most pacifists contended, that wars were forced upon a reluctant population by despotic and Machiavellian governments.” But the terrible truth of the matter is that the opposing armies of 1914-18 could never have gone on slaughtering one another with such dreadful efficiency had they not been given massive popular encouragement. For their principled opposition to this war, Russell was put in prison and Siegfried Sassoon sent to a mental hospital. And so European civilization was shattered and millions maimed or slaughtered, ostensibly because a student murdered an Archduke in a sleepy Balkan town not far from here. It is not just the prospect of gaining the spoils of victory that has attracted generations after generations to go to war, but the activity itself: war brings out both the best and the worst in us, mobilizing our deepest resources of courage, cooperation, loyalty and self-sacrifice, and releasing our capacities for xenophobia, hate, brutality, sadism and revenge. A vividly evocative memoir of World War II is The Warriors by the ex-soldier Glenn Gray (1998). While unsparing in his descriptions of the horrors of modern warfare, he nevertheless writes eloquently of its “powerful fascination” and the “confraternity of danger” which forges bonds between people with otherwise incompatible desires and temperaments. “At its height”, he writes, “this sense of comradeship is an ecstasy... Some extreme experience - mortal danger or the threat of destruction - is necessary to bring us fully together with our comrades... Comradeship reaches its peak in battle.” Thus, as a species we exist in the grip of a terrible paradox. Although in our saner moments we hate war as lethal, brutal and cruel, it is, from time to time, irresistibly seductive. As a result, armed conflict has repeatedly afflicted every part of our planet where human beings have come into contact with one another - not only in recent times but, in all probability, since our species came into existence. For conflict is endemic in the human condition, a manifestation of our willingness to polarise things into opposites, to make preferences and to take sides. Von Clausewitz’s notorious definition of war as “a continuation of policy by other means” implies that the policy to be continued is one based on conflict which then spills over into war. Our evolved propensities which make warlike behaviour possible, essentially unchanged since palaeolithic times ( Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1979; Tiger 1971; Stevens, 2004), continue to prompt men to seek aggressive confrontation in groups, motivating modern soldiers and terrorists, armed with weapons of unprecedented destructiveness, to slaughter their enemies in much the same spirit as Stone Age warriors (Fox, 1982). What I am arguing is that if we are to understand how, when, and why wars begin and why they have to recur, we must look a good deal further than history, with its restricted time scale and its neglect of the human unconscious. As the archaeologists and anthropologists have established, our capacity for warfare is much older than history. Homo sapiens has been in existence for 500,000 years, while history derives its data from a wafer thin layer of the recent past. When we adopt a perspective which includes our natural history as a species as well as our political history as civilized people, it begins to appear that the causes attributed to past wars by historians are not really causes at all, but merely the triggers that set them off. For war to become more attractive than peace, a fundamental transformation has to occur both in society and the minds of individuals - particularly in the minds of men. Women do not delight in banding together to train and arm themselves for battle; men do. The bonding of young males for aggressive pursuits is not so much an instinctual “urge” as a psychophysical disposition which can be activated, disciplined and exploited by more senior males in positions of authority (Stevens, 2004). This has been done again and again in practically all the societies known to anthropology (Tiger, 1971). It is as if there lurks a warrior archetype in the masculine unconscious, which can lie quiescent and inactive, rather like a nuclear missile in its underground silo. Unfortunately, the archetype, like the missile, can be activated. The necessary rituals for turning young men into warriors have been known and practised by human societies for millennia (Keeley, 1996; Stevens, 2004) and are still practised, little altered, in the training of modern warriors throughout the world to this day (Tiger, 1971; Hockey, 1986).

How do wars begin?

When a German Führer wishes to conquer the continent of Europe, a British Prime Minister to repossess the Falkland Islands, or an American President to invade a Middle Eastern country, they all have one thing in common: They do not go off and do it themselves. They persuade other people to do it for them. How on earth is this possible? Why do their people not laugh at them and tell them that if war is what they want they know what they can do - and then leave them to get on with it? Why, instead, do their countrymen say, “Yes, sir” (or “Ma’am”), buckle on their equipment, and march off to the front to be slaughtered in their hundreds, thousands, or millions? and why do dear ones left at home allow them - nay, encourage them - to go off and do it? A leader who wants to start a war needs to convince his army that it must fight and to persuade his people that to fight is a good idea. Given the horrific nature of modern warfare this would appear to be a tough undertaking. Yet the fact is that the leader who wants his war usually gets it. What is the trick? At his Nuremberg trial, the Nazi war criminal Hermann Goering described how easy it is to organize a war: “Why, of course,” he said, “the people don’t want war. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of a country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the peacemakers for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger.” Ten days before he invaded Poland in 1939, Hitler summoned his commanders-in-chief to the Berghof, his mountain retreat above Berchtesgaden; “I shall give a propagandist reason for starting the war,” he told them, “no matter whether it is plausible or not. The victor will not be asked afterwards whether he told the truth or not, When starting and waging a war it is not right that matters, but victory. Close your hearts to pity,” he exhorted them. “Act brutally.” The transformation of a community from the peaceful to the warlike state follows essentially the same pattern whether the community be one of baboons or Britons, anthropoid apes or Americans. When any primate community is observed over a long period of time it is found that periodically a striking alteration will occur from one state of collective organization to another. The anthropologist Anthony Wallace (1968) has called these, respectively, the relaxed and the mobilized state. In the relaxed state, individuals can be observed indulging in a variety of playful, sexual, educational, and economic activities. In the mobilized state, however, the population organizes itself into three broadly distinct groups - which Wallace designated the policy makers, the young males, and the females and children - the purpose being to cooperate under a recognized authority for the achievement of a definite aim, such as travel, hunting, or physical conflict. Most important of all, progression from the relaxed to the mobilized state is accompanied by a profound psychic change in individual members of the community - which is entirely compatible with the condition which Jung described as “archetypal possession.” Archetypal possession occurs when an archetype is activated in the unconscious with such intensity that ego consciousness falls under its power, with the result that the individual’s behaviour, feelings, and attitudes undergo a radical alteration. One of the commonest forms of archetypal possession, which I guess many people in this room will have experienced, is that of “falling in love.” Describing the transition from peace to war in sociological terms, Gaston Bouthoul of the Institut Français de Polémologie said: “In the transition from peace to war - and vice versa - we move from one social universe to another; all moral and material values, beginning with those affecting human life, are reversed. Whereas lengthy deliberation is needed before the worst criminal can be convicted, innocent young men with the future before them are sent to their death by the thousands without a moment’s hesitation. Economic values, too, are turned upside-down; people who are angered by a broken window-pane find it quite natural that whole towns should be destroyed.”

What brings the transformation about?

For the necessary transformation to occur, the population must receive what Wallace has termed the “releasing stimulus.” This must be issued loudly and clearly by an individual or group of individuals perceived as possessing the authority to issue it. And it must be issued in such a way as to convey conviction and emotive power to the populace. Hence the tendency in all human communities to follow up the rallying “call to arms” with political harangues presenting the “reasons” which make war “inevitable”, exhortations to steadfastness and valour, and the attendant use of bugles, trumpets, flags, drums, war dances, and all the stirring panoply of war In small pre-literate communities the releasing stimulus could be quickly and easily administered. The larger the group, however, the more complicated a matter mobilization becomes. The mobilizing order is more difficult to modify or countermand it once it has been issued - as the nations of Europe discovered to their terrible cost in 1914. (Observing Hitler’s actions in 1939, Kaiser Wilhelm II said: “The machine is running away with him as it ran away with me.” In modern societies the media play a vital role in arousing and sustaining the warlike state and in promoting what Gregory Bateson (1978) called schismogenesis - the pulling apart from the antagonistic group, and the vilification of the enemy. The easiest kind of war to start and to sustain is one against enemies of different race or colour, particularly when they speak a different language or have a different religion. The reason is that people of different race can be much more readily pseudospeciated – i.e. reclassified and treated as if they belonged to a species quite different from our own. Leaders can more easily persuade their population that such enemies are so unreasonable, malevolent, and different that it is not possible to treat them as normal human beings, and that the only language such people understand is the language of superior physical force. An appropriate state of paranoia can then be generated by cutting off all normal exchanges with the enemy population so as to eliminate any inconvenient fellow feeling that may remain.

Species and Pseudospecies All mammals and primates make a distinction between aggression against their own species and aggression against other species. In fighting their own kind they stop short of inflicting serious injury or death. The biological purpose of this is to prevent reduction of the size of the population. The implications of all this for the psychology of human warfare are highly instructive because men make a similar distinction. Humans not only differentiate between themselves and other species, but also make a clear distinction between the kind of aggression directed against members of their own population and the kind of aggression directed against members of other human groups. There is, for example, a tribe in Brazil called the Mundrucus, who make a distinction between themselves, whom they call “people”, and the rest of the population of the world, whom they call “pariwat”. These pariwat rank as game; they are spoken of exactly in the same way as huntable animals. The Mundrucus are not alone in their ethnocentric chauvinism. To a greater or lesser extent, all human communities do the same. This explains the distinction which human societies make between murder (which is universally regarded as bad) and killing in warfare (which is regarded as heroic). Indeed, it seems probable that our moral sense - what Freud termed the superego - possesses an innate dimension: the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” is respected in virtually all societies insofar as it applies to members of the in-group. Members of out-groups, however - the “Philistines”, the “uncircumcised”, the “pariwat” - are regarded as fair game. The Old Testament Commandment “Thou shalt not kill” really means “Thou shalt not kill Israelites”. The terms “in-group” and “out-group”, introduced by William Graham Sumner of Yale University nearly 100 years ago, have survived because they reflect a fundamental distinction at the heart of the social program of our species. It is the out-group that we can all too readily come to perceive as a “pseudospecies”, a term that was introduced by Erik Erikson at a meeting of the Royal Society in London in 1965. “Mankind from the very beginning has appeared on the world scene split into tribes and nations, castes and classes, religions and ideologies, each of which acts as if it were a separate species created or planned at the beginning of time by supernatural will.... Some of these pseudospecies, indeed, have mythologized for themselves a place and a moment in the very centre of the universe, where and when an especially provident deity caused it to be created superior to, or at least unique among, all others” (1984). There is no biological basis for pseudospeciation, in the sense that there are no different human species. However, there is a biological basis for our propensity to pseudospeciate; it is the propensity we share with all mammals to distinguish “us” from “them”. It is this pseudospeciating propensity that incites us to xenophobia, racism, militant nationalism, terrorism, and to war

Going to War

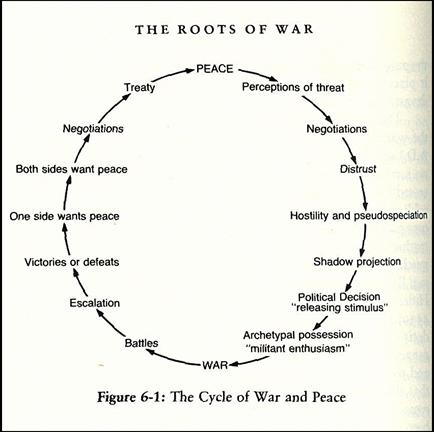

The stages through which the war-peace-war cycle moves can be represented in this diagram. Different sequences may operate in the genesis of different wars, some stages may be missed, and the sequence may at any stage be halted or put into reverse; but, on the whole, the sequence outlined here, or something similar, is followed in the genesis of most armed conflicts between groups of men, whatever the size of the groups and the power of the weapons at their disposal.

(1) Perception of threat: The first indication that the “relaxed state”of peace may be coming to an end is the perception by group leaders that the interests of some out-group are in competition with the interests of their in-group and that a possibility exists that this competition could become hostile. (2) Negotiation: In order to verify the situation, emissaries are exchanged and a phase of negotiation intervenes during which each group usually attempts to strengthen its interests at the expense of the other. (3) Breakdown and mistrust: Breakdown in these negotiations leads to an erosion of trust between the two parties which may be accompanied by the expression of hostile or threatening behaviour on the part of one or both sides. (4) Hostility and pseudospeciation: Powerful feelings of mutual antipathy coincide with a reinforcement of the perception by members of both groups that the other group constitutes a pseudospecies against which it would be legitimate to use organized group violence. (5) Shadow projection: As the process of mutual hostility and mutual denigration progresses, the archetype of the Enemy (Jung’s shadow archetype) is constellated in the psyche of members of each group and projected collectively on to the members of the other. Deteriorating relations render contact between the two groups both difficult and dangerous and, as a consequence, the possibility for testing the reality of mutual shadow projections is lost. The amount and intensity of shadow qualities attributed by each to the other therefore increases. What is activated and projected is not just the archetype of the Evil Enemy, but all that is repressed and rejected in the personal psyche of each individual member of both communities. The skillful leader will make use of this fact to wage a propaganda war against the adversary so as to build up aggressive feelings amongst his people and prepare them to respond to the order to move form the relaxed to the mobilized state. (6) Political decision: At this stage the political leaders of one or both groups must decide whether or not to issue the “releasing stimulus” and put the population on a war footing. Their decision will be influenced by strategic, tactical, and logistic considerations as well as by the extent to which they are themselves in the grip of their own power complexes or have fallen victims to their own propaganda. Should they give the order to mobilize, it will confirm the warlike anticipation which has already accumulated in the population and tip them over into a collective state of “possession” by the archetype of war. From that moment, their perceptions, values, beliefs, and customary patterns of behaviour will undergo a radical transformation. Konrad Lorenz has called this state one of “militant enthusiasm.” As Lorenz wrote, “The Greek word enthousiasmos implies that a person is possessed by a god, [and in the state of] militant enthusiasm...... one soars elated above all the ties of everyday life, one is ready to abandon all for the call of what, in the moment of this specific emotion, seems to be a sacred duty. All obstacles in its path become unimportant, the instinctive inhibitions against hurting or killing one’s fellows lose, unfortunately, much of their power.... Men may enjoy the feeling of absolute righteousness even while they commit atrocities. Conceptual thought and moral responsibility are at their lowest ebb. As an Ukrainian proverb says: “When the banner is unfurled, all reason is in the trumpet!” (1966). (7) Battle is joined: With the commencement of physical hostilities, the behaviour of each group is seen as confirming the validity of the shadow projection made by the other. Those warriors or soldiers whose aggressive feelings have not previously been stirred into consciousness now become aware of a desire to attack and destroy the enemy. This desire is powerfully intensified if enemy action should result in the death or severe injury of a comrade. Then feelings of group loyalty and personal commitment to the conflict are immeasurably strengthened. As Lorenz says, the most important prerequisite for the release of militant enthusiasm is the presence of other individuals all agitated by the same emotion. (8) Escalation: Physical hostilities persist and the commitment of one or both sides to the conflict increases in ferocity with a consequent escalation of the damage and losses suffered. (9) Victory or defeat: The war continues to be waged until one side scores a decisive victory or until such time as it is perceived as being to the advantage of one or both parties that hostilities should cease. (10) Restoration of peace: Negotiations are instituted which, if successful, result in the partial or virtually complete withdrawal of shadow projections and the resumption of normal diplomatic links. So to conclude: War remains the critical problem of our species. We cannot stop doing it, and yet we are armed with weapons that can destroy our planet and all life on it many times over. The problem overshadows that even of global warming. Great continental power blocks, armed to the teeth, competing for dwindling natural resources in a world growing ever hotter is a recipe for the most appalling series of disasters our planet has ever known. Yet we sleepwalk towards it in the same way as our grandparents and great-grandparents sleepwalked towards the disaster of WWI during the first decade of the last century. They had no idea what would hit them till it arrived.

References Bateson, G. (1978) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. London: Paladin Clausewitz, C.M. von (1976) On War, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Dixon, N.F. (1979) On the Psychology of Military Incompetence. London: Futura Publications. Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (1979) The Biology of War and Peace. New York: Viking. Erikson, E.H. (1984) ‘Reflections on Ethos and War’, Yale Review, 73, 4, 481-6. Fox, R. (1982) ‘The Violent Imagination’, in P. Marsh and A. Campbell, eds, Aggression and Violence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Fussell, P. (1975) The Great War in Modern Memory. New York, London: Oxford University Press. Gray, J.G. (1998) The Warriors: Relfections on Men in Battle. Lincoln, NB, and London: University of Nebraska Press. Hockey,J. (1986) Squaddies: Portrait of a Subculture. Exeter: Exeter University Publications. Keeley, L.H. (1990) War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Lorenz, K. (1966) On Aggression. London: Methuen. Rae J. (1960) The Custard Boys. London: R. Hart-Davis. Russell, B. (1967) Autobiography. London: George Allen and Unwin. Spaulding, O.L., Nickerson, H., and Wright, J.W. (1924) Warfare: A Study of Military Methods from the Earliest Times. London: Harcourt, Brace & Co. Stevens, A. (2004) The Roots of War and Terror. London: Continuum. Sumner, W.G. (1913) War and Other Essays. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Tiger, L. (1971) Mein in Groups. London: Panther. Wallace, A.F.C. (1968) ‘Psychological Preparations for War’, in M. Fried, M. Harris, and R. Murphy, eds, War: The Anthropology of Armed Conflict and Aggression. Garden City, New York: Natural History Press. Walsh, M.N. (1976) in M.A. Nettleship, R.D. Grivens, and A. Nettleship, eds, War, Its Causes and Correlates. The Hague and Paris: Mouton Publishers.

|

|

|||